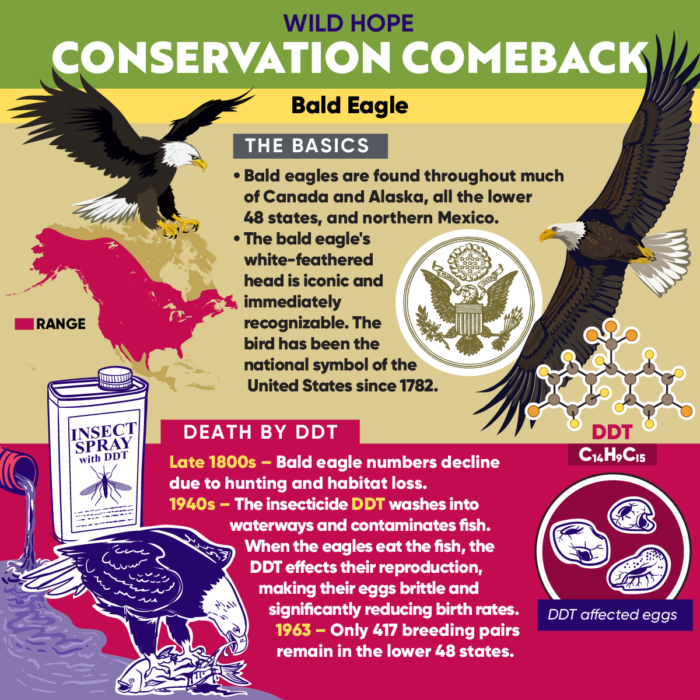

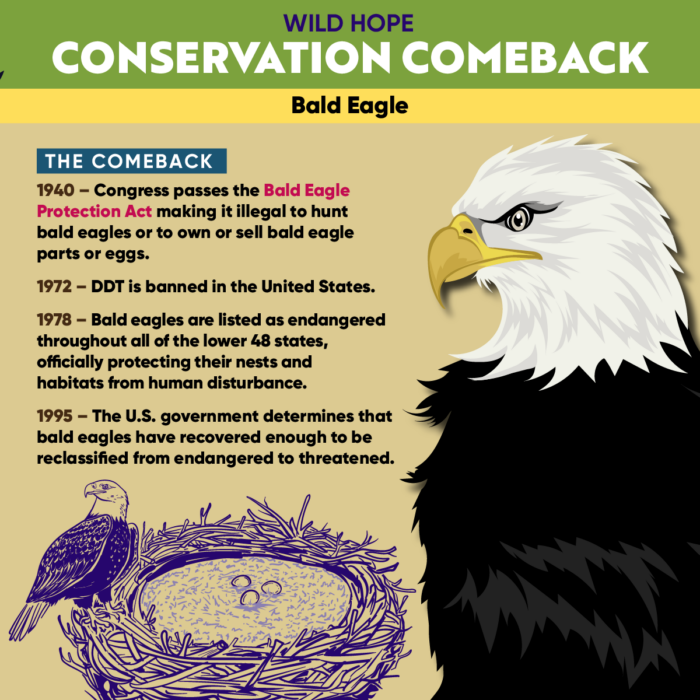

The bald eagle has been a national symbol of the United States since 1782 — but not that long ago, this iconic species was on the verge of a complete extinction. In the late 1800s the eagle population had already begun to decline due to hunting and habitat loss, but the real threat came in the 1940s with the introduction of the pesticide DDT. Chemical runoff would contaminate fish, and then once ingested by the eagles, would cause the eagles to lay brittle eggs that would break before hatching. In 1963, there were less than 500 breeding pairs in the lower 48 states.

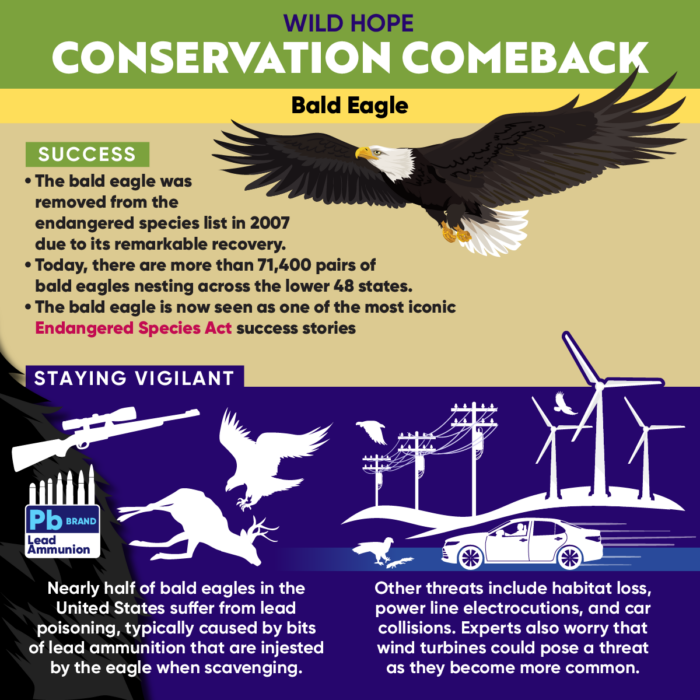

DDT was banned in 1972 and the bald eagle was officially listed as endangered in 1978, allowing their recovery to take off. Over the next 20 years, the population rebounded — and in 1995 the species’ was removed from the endangered species list entirely. Today, their numbers are thriving once again, with more than 70,000 breeding pairs of eagles observed in the lower 48 states. The bald eagle is seen as one of the most iconic Endangered Species Act success stories.

Explore more stories from the full Conservation Comeback series now.

Frog saunas could help fight chytrid, Iberian lynx are no longer endangered, and scientists in Hawaii are breeding heat-resistant corals.

Alecia has held many career positions, from software trainer to office administrator; however, outside of work she is heavily involved in volunteer associations focusing on education. Most recently, Alecia’s Clean Harbours Jamaica team has, in partnership with The Ocean Cleanup, removed over 1 million kg of garbage from the barriers and by extension from the […]

It’s estimated that up to 14 million tons of plastic end up in the world’s oceans every year—and 80% of it pours into the sea from polluted rivers. In Kingston, Jamaica, Alecia Beaufort and her team at Clean Harbors Jamaica have partnered with The Ocean Cleanup to stop the waste before it ever reaches the sea.

Golden eagles, bald eagles, and other North American raptors have made a remarkable comeback since the chemical pesticide DDT was banned in the United States in 1972. But they still face challenges to a full recovery. Learn more about golden eagles, and how you can support efforts to combat the threats they face.

Hannah was born and raised under the Big Sky in Montana and has enjoyed outdoor pursuits her whole life. With a bachelor’s in marketing and a master’s in resource conservation, she has a unique perspective on outreach efforts for the benefit of conservation.

For over 15 years, Bryan has been a leading scientist documenting the link between lead-based ammunition and ingestion in wildlife. He co-founded and is Director of Sporting Lead-Free to promote an unbiased, non-political message within our community about the benefits of using lead-free sporting options to preserve both our hunting heritage and amazing Wyoming wildlife.

Conservationist and hunter Bryan Bedrosian started Sporting Lead Free to offer a solution to the problem of lead poisoning in eagles: advocating for the use of non-lead bullets as a permanent substitute for traditional lead ammunition.

Nearly half of all golden eagles and bald eagles in the U.S. have elevated lead levels in their bodies. This lead poisoning comes from the bullets used by hunters — not because the bullets harm the eagles directly, but the birds do scavenge on “gut piles” laden with lead fragments left behind after successful hunts.

Black-footed ferrets are still alive today thanks to the combined efforts of scientists, zoos, tribes, and other partners across North America. The work hasn’t been easy — it’s involved a decades-long captive breeding effort, wild releases at 30 different grassland sites, and even the development of a vaccine to protect against plague! It’s been a […]

Black-footed ferrets nearly went extinct several times in the 20th century. Today, the current largest threat to their survival is a non-native disease called sylvatic plague.

When plowing, poisoning, and non-native plague wiped out nearly 95% of prairie dogs, the ecosystem collapsed around them. Today, conservationists control the disease by providing vaccine-laden treats called “Fip Bits” to help the prairie dogs — and those that depend on them — finally rebound!

With over 25 years of experience in the wildlife field, Kristy Bly’s expertise is on the conservation and restoration of black-footed ferrets, black-tailed prairie dogs, and swift fox in the North American Great Plains.

Hope for Hawaiian honeycreepers, beavers in London, a snake's triumphant return, and rewilding on college campuses.

Callie Veelenturf is a marine conservation biologist specializing in sea turtles, the founder of The Leatherback Project, and a National Geographic Explorer.

Aida Magaña Manzzo is a nautical engineer and community leader for the Saboga Wildlife Refuge. She has been recognized as a Hope Spot Champion for her marine conservation efforts in the Pearl Islands.

The Pearl Islands were a paradise off the Pacific coast of Panama, until industrial fishing fleets threatened fish stocks and endangered wildlife there. Local residents have teamed up with biologist Callie Veelenturf to propose—and pass—a new national law that grants legal rights to nature itself.

Marine biologist Callie Veenlenturf came to the Pearl Islands to study sea turtles, but soon helped spark passage of remarkable laws that grant legal rights to nature and the turtles themselves.

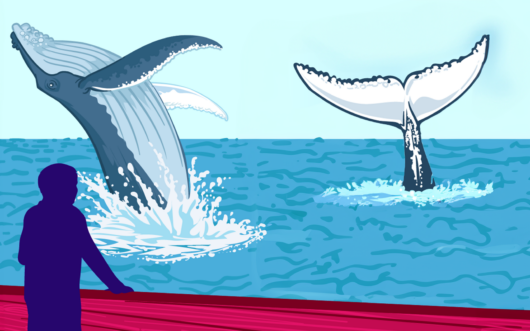

Humpback whales are truly a global species. These mammals have one of the longest migrations around, traveling up to 10,000 miles in a single year — and their beautiful, complex songs are heard by sailors and tourists in every corner of the globe.

Sea otters are a marine mammal beloved by many, but it wasn't long ago that they teetered on the brink of extinction. The international fur trade decimated sea otter populations starting in the 1700s, and by the early 1900s, their wild population fell to less than 1% of their original numbers.

More than 35% of land in Belize is protected, and that’s been good for jaguars that live in these refuges — but for populations to thrive, the cats need to move from one safe area in the north to another in the south across a landscape of farms and towns.

Upcoming: Episode 28: Cougar Crossing

Los Angeles is well known for its celebrities, so when the fearless cougar P-22 gained fame for making its home in the midst of the city, he inspired an effort to build the world’s largest wildlife crossing and helped spark a national campaign to support crossings and corridors everywhere. After years of research, local biologists and advocates like Beth Pratt pinpointed the vital location for a wildlife crossing to be built to restitch an entire ecosystem. Now a decade later, P-22’s story continues to inspire the very construction of this landmark crossing and expands what’s possible for urban wildlife coexistence.

At the age of 18, Boyan Slat founded The Ocean Cleanup and set out to clean plastic from the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. Ten years later, the team is installing catchment systems at the mouths of rivers to stop plastic pollution of the seas at their source.

Golden eagles are powerful enough to hunt prey as large as deer, but they’re falling victim to deadly lead poisoning introduced to the wild by another potent hunter: us. Across the nation, fragments from lead bullets in the entrails hunters leave behind are poisoning eagles and the other wildlife that scavenge them. But there’s a simple solution — copper bullets — that prevent the birds and even the hunters themselves from being exposed to the deadly metal.

Jaguars are top predators that need large spaces in which to live and hunt. In Belize, 35% of the land has been protected—but these areas are divided into two large clusters, connected by a crucial and dangerous bottleneck that the cats must navigate to survive.

Black-footed ferrets have come back from near extinction thanks to breeding, cloning and reintroduction programs that have brought them back to the western prairie. Now, these wild populations are threatened by a plague that targets the prairie dogs they depend on for food — and even the ferrets themselves. The best chance? To vaccinate both predator and prey to keep both populations alive.

Personhood for whales, a big conservation study, and egg-citing news for sea turtles

Emma Sanchez is a wildlife researcher and the country coordinator for Panthera Belize, an organization that pioneered jaguar research and established the first official protected area for jaguars.

Ray Cal is a wildlife ecologist and the manager of Runaway Creek Nature Reserve in central Belize. He is in charge of field operations and maintaining security, so that Runaway Creek continues to stay a model wildlife haven.

With just a few changes, you can transform your yard or balcony from a wildlife desert into a wildlife sanctuary. And, if you convince your neighbors to do the same, you could even make your neighborhood into a habitat corridor for wildlife!

Just like humans, wild animals often need to cross busy roads as they roam. But unlike us, they can’t rely on stoplights and crosswalks. That’s where wildlife crossings come in.

Wildlife corridors are an invaluable conservation tool. These ribbons of habitat connect landscapes fragmented by human development or roadways, giving animals the ability to roam in search of food, water, and mates.

In Brazil’s Atlantic Forest, Mauricio Ruiz has turned his love for nature into action by working with the community to reforest a critical stretch of the nation’s most endangered forest, and by using drones to help him reach his goal of planting 15 million trees.

In order to scale up reforestation, Mauricio Ruiz and his organization ITPA have partnered with the drone fleet at MORFO. Each drone can plant up to 50 hectares of forest per day, which is 50 times faster than planting by hand.

Deep in the Panamanian forest, researchers are looking for “lost frogs” — species believed to have gone extinct, but that may be holding on in the wild.

In the heart of Panama, scientists have created an artificial rainforest to protect endangered frogs from the worst wildlife disease ever recorded.

Harlequin frogs (also called harlequin toads) are a group of beautiful, brightly-colored toads found in Central and South America. One species in particular, the Panamanian golden frog, is considered the national animal of Panama and a flagship species for amphibian conservation.

Dr. Gina Della Togna is the Executive Director of the Amphibian Survival Alliance and a Research Associate of the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute.

Brian Gratwicke is a conservation biologist who leads the amphibian conservation programs at Smithsonian's National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute.

Plants can’t move on their own, so they usually need a little help to spread their seeds far and wide. Animals that scatter these seeds — often by eating the fruit and pooping out the remains — are known as seed dispersers.

Over 50 species of honeycreeper once lived in Hawai’i, but now only 17 species remain after battling against invasive species and habitat loss. Today, even those survivors are threatened further by avian malaria. To stop the disease, conservationists use innovative techniques to suppress the population of the invasive mosquitoes that spread it.

Millions of years ago, a single rosefinch species arrived on the Hawai’ian islands and evolved into over 50 species of honeycreepers — a phenomenon known as adaptive radiation.

Hawaiian honeycreepers are a group of songbirds endemic to the Hawaiian islands, all descended from a single species that arrived from the mainland six to seven million years ago. They are considered a dramatic example of adaptive radiation, a phenomenon in which a single species rapidly diversifies into many different ones. At one point, there were more than 50 different honeycreeper species on the islands, each sporting its own unique coloration, beak shape, and diets.

One of the major threats to Hawaiian honeycreepers is a deadly, mosquito-borne disease called avian malaria. Similar to malaria that infects humans, the disease is caused by parasites that enter honeycreepers’ bloodstreams when they are bitten by a disease-carrying mosquito.

Hawai’i is home to a broad, beautiful array of birds species found only on its islands—like the stunningly diverse honeycreepers, many on the border of extinction. Now, a local team is removing invasive predators, restoring habitats, and battling mosquito-borne diseases to protect honeycreepers from their latest threat: avian malaria.

Christa Seidl is a disease ecologist with over 10 years of experience leading research and conservation projects in Hawai'i, Aotearoa (New Zealand), Madagascar, Ecuador, and California with private, public, and industry partners.

Laura Bertholdis an Avian Research Field Supervisor at the Maui Forest Bird Recovery Project (MFBRP) assisting with planning and implementing research and management projects for native honeycreeper and forest recovery.

In addition to the impact of avian malaria, Hawai’i’s endangered honeycreepers are threatened by habitat loss and invasive predators — two problems that harm native bird populations everywhere, likely in your own back yard. Whether you’re looking to help Hawai’i’s birds, or if you’re hoping to make a difference to protect birds locally, the solutions […]

New tracking technologies are uncovering the flight paths of endangered shorebirds — and the obstacles they face along the way.

The endangered wedge-tailed shearwater — also known as the ‘ua‘u kani — was in critical danger after many nesting sites in Hawaii were overrun by predators like weasels, rags, or feral cats. Fortunately for the birds, locals banded together to protect nesting sites and the local population went from just 30 nesting birds to more than 3000!

A group in Maui has restored a safe haven for endangered seabirds to come home and nest: it’s completely fenced-off from predators and restored with native plants, but the birds still need some convincing! The team is using decoy “neighbors” and audio recordings of bird calls to make the seabirds feel at home — and at long last, the colony is growing!

All around the world, seabirds provide a critical link between land and sea. On Hawai’i, ecologists are working to protect two vital shearwater species that helped life first take hold on these islands.

Seabirds like those in Hawai'i have been given a second chance by the volunteers, scientists, and communities that lead the work to reverse their decline. While these birds — and the threats they face — may be unique to islands in the Pacific, the work to protect birds of a feather can be found anywhere around the globe.

Jay Penniman has worked as an independent contractor doing forestry, wildlife, and vegetation surveys, management, and assessment. Since 2006, he has worked for the Pacific Cooperative Studies Unit of the University of Hawaii managing the Maui Nui Seabird Recovery Project.

Jenni Learned is a broad-spectrum ecologist on the Maui Nui Seabird team with experience working across diverse environments.

A common conservation technique on islands is the creation of predator-free zones to exclude invasive species, from mice to feral pigs, from recovering habitats.

Some species at the center of conservation efforts — like seabirds — are inherently social animals. Scientists can take advantage of this affinity to woo them back to their old haunts — or to newer, safer nesting sites.

Coral reefs around the world are threatened by rising ocean temperatures, but hope is growing off the coast of Hawaii. There, researchers at the Coral Resilience Lab selectively breed corals to withstand ever-increasing amounts of heat stress.

This community in Hawaii is rallying together to study and protect local corals. Students, volunteers, and scientists work to collect and categorize fragments broken off from the reef, which then become candidates to breed before the new coral is reintroduced back into the ocean.

Corals are vital to ocean health, but they’re susceptible to rising water temperatures and can “bleach” under too much heat stress. Hawaii’s Coral Resilience Lab is breeding corals that are resilient to these hotter ocean temperatures – then they populate reefs with new corals that can finally beat the heat.

Coral reef bleaching stands apart as a crisis with innovative, long-term solutions.

Kira Hughes is the Managing Director of the Coral Resilience Lab at the Hawaiʻi Institute of Marine Biology. This includes conducting research, grant writing and administration, engaging stakeholders, establishing and maintaining partnerships, and communicating science.

Madeleine Sherman is the Project Manager for the Coral Resilience Lab at the Hawai‘i Institute of Marine Biology, and manager of the Lab's outreach and education programs.

Since the Endangered Species Act was passed in 1973, it has become one of the most powerful tools to fight extinction in the United States.

The California condor is a North American wildlife icon — the continent's largest land birds and one of nature's most industrious scavengers — and also one of our most critically endangered avian species.

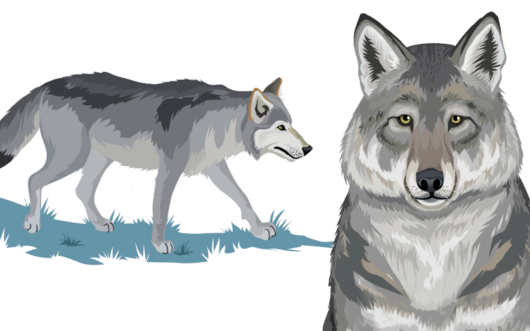

Our relationship with gray wolves is a complicated one, spanning centuries of tension and dating back to the beginning in the 1600s with North American colonization.

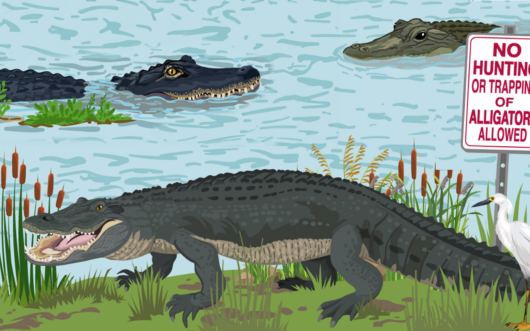

The recovery of the American Alligator is considered one of the biggest success stories of an endangered species – ever.

Along the Pacific coastlines of North America, the Northern Elephant Seal may be a common sight in today's waters — but that wasn't always the case.

Florida manatees are in dire straits, having lost much of their available habitat and food sources in recent decades. Thanks to the work of Zoo Tampa and other researchers, the population is finally able to recover and return to the rivers they once called home.

Florida’s Crystal River used to be a rich seagrass ecosystem: a perfect source of food for the many manatees that once thrived there, before an invasive algae overtook the riverbed. Now, efforts to restore the habitat are underway – and they’re working!

When an invasive algae in Crystal River wiped out the eel grass that manatees need for food, the community rallies to restore the river and save the animals that call it home.

Lisa Moore, a fourth-generation Floridian, is an entrepreneur and philanthropist dedicated to the efforts to preserve, protect, and restore environmental resources.

Jessica Maillez is the Senior Environmental Manager at Sea and Shoreline. She has designed, permitted, and managed multiple large scale restoration projects along Florida’s coastline.

The United Kingdom and Ireland might not seem like the wildest places on Earth, but a growing popular movement here, known as rewilding, seeks to reverse millennia of environmental degradation.

Derek Gow has turned his farm into a breeding center to help rewild all of Britain. He’s raising rare white storks, native harvest mice, water voles that can help restore wetlands throughout the country.

Derek Gow has helped bring beavers back to Britain, and their impact on local landscapes and biodiversity has been immense. Now, he’s scaling up a breeding program to export another wetland engineer—the water vole—all across the country.

For years, Derek Gow worked his 400-acres in western England as a conventional sheep and cattle farm. Now, he’s using his experience with British rewilding projects to return his land to what it once was: a healthy, biodiverse ecosystem.

Ecologists from Mexico’s National Autonomous university relaunch a fundraising campaign to bolster conservation efforts for axolotls, an iconic, endangered fish-like type of salamander.

Pete Cooper is a wilding ecologist at the Derek Gow Consultancy, where he works on a variety of species reintroduction and rewilding projects. He leads a project trialing the captive breeding and reintroduction of glowworms, as well as working closely on reintroduction projects for other species including the harvest mouse, wildcat and turtle dove.

Derek Gow is a farmer, nature conservationist, and the author of Bringing Back the Beaver. He lives on a 300-acre farm on the Devon/Cornwall border, which he is in the process of rewilding. Derek has played a significant role in the reintroduction of the Eurasian beaver, the water vole and the white stork in England.

Often the first and most effective strategy to healing a landscape is to pay attention to how ancestral wildlife, like native plants and animals, once shaped and strengthened these natural spaces.

Just as they have for millions of years, sea turtles by the thousands make their labored crawl from the ocean to U.S. beaches to lay their eggs. This year, record nesting was found in Florida and elsewhere despite growing concern about threats from climate change.

Leatherback turtles never stop swimming! This Florida lab uses tiny tethers so young hatchlings can swim constantly but avoid bumping into the wall of the tank. When they’re old enough, the young turtles are fitted with satellite trackers and released into the wild.

Beaches across Florida are a key habitat for nesting sea turtles. To keep hatchlings safe, teams patrol the beach at dawn to look for turtle tracks, safeguard nests, and even help those left behind make their way to the sea.

Sea turtles nesting in southeast Florida face a range of manmade threats — and for leatherbacks, researchers still know very little about the species and how to protect them. In the battle to save leatherback sea turtles, knowledge is key.

David Anderson is the Sea Turtle Conservation Coordinator at Gumbo Limbo Nature Center. He supervises the collection of sea turtle nesting data along Boca Raton’s five miles of beach.

Dr. Jeanette Wyneken is a Professor of Biological Sciences at Florida Atlantic University (FAU), located on the southeastern coast of Florida. She has more than 40 years of experience studying the biology, conservation, and health of sea turtles.

Whether becoming a citizen scientist, or simply a vocal ally for sea turtle protection, there are easy opportunities for anyone to get involved in saving some of our favorite ocean-bound creatures.

In 2021, an Oregon farmer decided to convert his 400-acre farm back to the wetland habitat. Now, just two year later, the new wetland supports migrating waterbirds and endangered fish.

Indigo snakes prey on other snakes—even venomous ones—but are still docile-enough to be handled by young children. Now, a one-of-a kind breeding program is raising these gentle giants and returning them to forests across the southeastern US.

Gopher tortoises create deep burrows that give critical shelter to over 350 species of insects, mammals, birds, and amphibians throughout the southeastern US. Their blood may be cold, but their heart is all warm inside!

In the face of extreme habitat loss, wildlife biologist Dr. Chris Jenkins puts an ambitious plan in motion to save two uniquely American reptiles — the eastern indigo snake and the gopher tortoise — and the longleaf pine forest they call home.

Dr. James Bogan is the Director for the Central Florida Zoo’s Orianne Center for Indigo Conservation, the only facility that breeds the eastern indigo snake for the sole purpose of reintroducing the offspring into regions where the population is believed to be locally extinct.

Christopher Jenkins has worked with Wildlife Conservation Society, the U.S. Forest Service, and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. His current projects include land protection in longleaf pine ecosystems, ecology and conservation of timber rattlesnakes and the conservation of giant tortoises.

Reptiles are in need of support from conservationists and nature-lovers worldwide. Learn how to create more reptile-friendly environments and help build a stronger ecosystem for all types of critters near you.

Honeycreepers are a diverse group of birds found only in the forests of the Hawaii Islands, where they thrived for millions of years. But now, some species may disappear within the decade thanks to a growing threat: avian malaria.

After decades of fighting to regain ownership of their ancestral lands, the Winnemem Wintu Tribe marked this year’s Indigenous People’s Day with the purchase of 1,080 acres of land along the McCloud River in northern California.

When beavers were hunted to extinction in England some 400 years ago, the wetlands they maintained largely vanished. Now, as part of Britain’s broader rewilding mission, conservationists are returning beavers to the landscape—and boosting biodiversity in the process.

Prince William got a first-hand look at the waters of New York City on Monday on a visit to an oyster reef restoration project, after arriving in the United States for an environmental summit connected to a global competition for solutions to climate change challenges.

A century ago, the longleaf pine forests of the southeastern United States were flooded with birdsong—and the musical hammering of millions of red-cockaded woodpeckers. But by 1995, deforestation had caused woodpecker numbers to plummet to 4000 breeding groups.

Biologists in Mexico are learning how to save endangered salamanders by partnering with unusual allies: a group of nuns.

Axolotls can regenerate entire limbs, eyes and even their brains—and make a great “second date love” for one scientist.

The axolotl has been called a “conservation paradox” — a creature that is ubiquitous in pet stores, science labs and pop culture… yet almost extinct in the wild.

The axolotl is a type of salamander native to the canals and lakes around Mexico City, characterized by its flamboyant, feathery external gills.

Carlos Uriel Sumano Arias is a researcher with the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM).

Luis Zambrano was born in Tampico, Mexico, and earned a degree in biology from the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM). He obtained his doctorate in ecology at UNAM, studying the effects of carp on benthic communities in experimental ponds. Zambrano’s research specialities are aquatic ecology and restoration. A founding member of the Mexican Society […]

A group of women in Mozambique risked their lives to save thousands of coffee plants they knew would bring a better life for their families—and help restore a watershed that people and wildlife depend on.

A man in Mozambique helps local farmers grow native trees to provide shade to the coffee crops they depend on—and restore a rainforest for people and wildlife alike.

Marcos Bera Chova is the manager of the reforestation and honey programs on Mount Gorongosa. He joined Gorongosa National Park in 2012 as a reforestation specialist and forest technician.

Sional Sérgio Moiane, known as Sunyl, has been working with Gorongosa National Park since July 2014. He is the lead supervisor of the coffee sector in Mount Gorongosa. He is passionate about his work even in situations of conflict on the mountain, and his objective is to see communities develop economically through the production of […]

To save Gorongosa National Park's wilderness, these teams are trying something new: encouraging people to plant a cash crop—shade-grown coffee—that actually depends on restoring the forest to thrive.

At Gorongosa National Park, scientists are determined to understand how an ecosystem recovers from the decimation of war.

NASA satellite imagery has recently been able to show that beavers banished to rural Idaho have made significant improvements to waterways in the region.

The communities around Gorongosa National Park have been investing for decades in eco-friendly agriculture (like sustainable, shade-grown coffee), as well as research-driven wildlife management and the building of an economic framework that supports both the Park's natural ecosystem and its surrounding communities.

Removing dams from the Elwha River allows salmon to return upstream—and bring precious nutrients from the sea that eventually spread throughout the forest.

For decades, the Lower Elwha Klallam tribe fought to remove unwelcome dams on their river—and finally won.

A century-long campaign to take down the Elwha River dams climaxed in 2011with the largest dam removal project in history. Now, a decade later, Native American scientists and colleagues are chronicling an inspiring story of ecological rebirth.

From the revitalization of riverbeds to the genetic diversity of top predators, Kim Sager-Fradkin is tracking an ecological resurrection in Washington’s Olympic Peninsula.

Inspired by the success of the Elwha dam removal model, conservation advocates are building diverse coalitions to pursue additional salmon recovery projects across the Pacific Northwest region.

Ecuadorians voted against drilling for oil in a protected area of the Amazon, an important decision that will require the state oil company to end its operations in a region that’s home to two uncontacted tribes and is a hotspot of biodiversity.

The Reserva Land Trust has rallied together young people from across 25 countries to create the world’s first youth-funded nature reserve in Ecuador.

Ecuador is one of the most biodiverse places on the planet— and the first country in the world to enshrine the “rights of nature” in its constitution.